In response, Congress passed a bill allowing veterans to cash in part of their IOUs as loans. Angelo walked four days from his home in New Jersey to Washington to demand the bonus be paid immediately. When the Great Depression hit, many veterans realized their green-bordered bonus certificates was their only asset that still held any value.

But there was a catch: if the sum was more than $50, it would only be paid to the veteran’s survivors after they died or in 1945, whichever came first. In 1924, Congress had finally passed a bonus bill over President Coolidge’s veto, mandating that most who served during the mobilization would get $1 of back pay for each day of home service and $1.25 for each day abroad. Many had come home from Europe to find their savings drained and jobs gone. The cause that drew them was known as the “bonus.” Veterans’ benefits had been minimal in the last World War.

By July, there were some forty-five thousand veteran protesters, wives, and children living in shacks in the shadow of the Capitol dome. Calling themselves the Bonus Expeditionary Force, they set up encampments across Washington. Over the spring of 1932, veterans from every corner of the country began making their way to Washington, D.C.

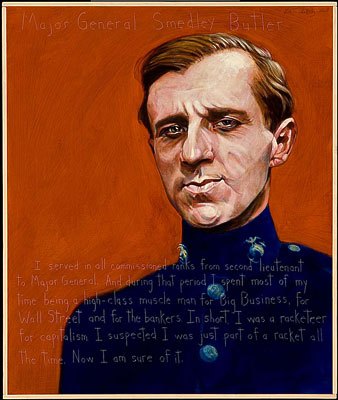

(Still from Fox Movietone News outtake, Moving Image Research Collections, University of South Carolina) Butler addressing the Bonus Marchers in Anacostia Flats, Washington, D.C., July 19, 1932. That man, standing lonely astride the lens-shaped center of a peculiar Venn diagram, has the unlikely name of Smedley Darlington Butler.Smedley D. Among those, there is probably only a single person who will be discovered almost exclusively by two generally nonoverlapping groups: avid readers of the corpus of Noam Chomsky, and members of the Marine Corps. They are most likely to be encountered, if they are encountered at all, in the institutions that often engage the attention of young people between the ages of 18 and 22. But there is also a group of people who have not passed into national legend, and perhaps whose lives are not considered fit to explain to children. There are some figures whose place in the story of the American past is so central that schoolchildren cannot help but know them: George Washington, or Abraham Lincoln, or Rosa Parks. I have a review in the January/February issue of The New Republic of Jonathan Katz’s biography/travelogue of Smedley Butler, a figure of long fascination to many and totally obscure to others.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)